Artificial Intelligence and Politics

A first pass at mapping (the story of the next decade?) all of the changing political terrain of AI

Note to the reader: This is a (very) long, integrative, and at times speculative brain dump on the coming politics of AI.

I’m putting on my political scientist hat and trying to pull together a lot of different threads, so please treat this as terrain mapping rather than a settled argument.

AI is moving quickly from a research project on a few servers into something that will shape everyday life—and, soon enough (if not already), everyday politics.

The core claim is simple: AI will become politicized less because of new ideologies and more because it will activate existing cleavages and stress institutions that already struggle to command trust. Everything that follows in this is really downstream of that.

So buckle up. Get comfy. This will likely take more than one pomodoro.

The Coming Politicization of AI

Artificial intelligence has mostly been framed as a technology story—breakthroughs, productivity gains, existential risk debates. That framing is not going to survive contact with democratic politics.

AI is moving from a research agenda into distributional conflict. And in political science, distributional conflict is where the real action always is—everything else is window dressing.

The question is not whether AI is transformative. The question (as it always is in political science anyway!) is who bears the costs, who captures the benefits, and which institutions people trust to referee those fights when they inevitably break out.

What makes AI different from prior waves of technological change is not just capability. It is speed.

Diffusion at an Unprecedented Pace

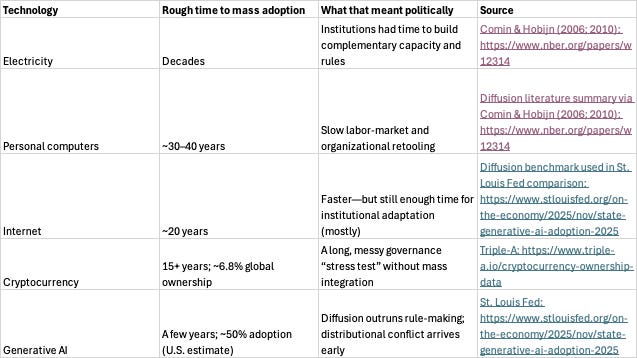

General-purpose technologies have always reshaped politics, but they usually diffuse slowly. Electricity, telephones, personal computers, and the internet took decades to reach mass adoption, which gave institutions and political coalitions time—sometimes grudging time—to adapt.

Generative AI is compressing that process into a handful of election cycles.

A Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis analysis estimates that generative AI reached roughly 54.6 percent adoption within a few years of introduction—far faster than personal computers or the internet at comparable stages of diffusion.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2025/nov/state-generative-ai-adoption-2025

Industry estimates suggest more than half of U.S. adults have used generative AI tools, with nearly one in five using them daily.

https://menlovc.com/perspective/2025-the-state-of-consumer-ai/

Globally, roughly one in six people were using generative AI tools by the end of 2025, with rapid growth in emerging markets that may leapfrog legacy computing infrastructure.

https://explodingtopics.com/blog/ai-statistics

This is historically unusual. AI is not diffusing through hobbyists and early adopters. It is diffusing through classrooms, offices, and everyday workflows. Our institutions have never had to absorb a cognitive general-purpose technology moving this fast.

Diffusion speed by itself does not politicize technologies—smartphones spread quickly without producing immediate polarization. What makes AI different is that rapid diffusion is colliding with visible distributional shocks: job ladders shifting, power grids straining, and capital concentrating in a small set of firms. Diffusion is the accelerator, not the only cause.

Sidebar: Why Diffusion Speed Matters (Rogers, Mansfield, Comin & Hobijn)

Everett Rogers’ classic Diffusion of Innovations model (Rogers 1962; 2003) describes adoption as an S-curve: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards. Historically, that curve unfolds over decades.

Empirical work by Mansfield (1961), and later Comin and Hobijn (2006; 2010), shows that most technologies diffuse slowly, with later work emphasizing the role of complementary investments in infrastructure, skills, and institutions.

Comin and Hobijn’s work documents multi-decade adoption curves for electricity, telephones, and personal computers.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w12314 and https://www.nber.org/research/data/historical-cross-country-technology-adoption-hccta-dataset

Generative AI breaks this pattern. At over 50% adoption (in the US), we are already technically in Rogers’ late majority phase!

The point is that institutions historically co-evolve with technology at the pace of diffusion. When diffusion accelerates, institutional adaptation lags. The result is policy made on the fly, without a stable theory of the case.

Crypto, which will be a comparison throughout this discussion, diffused slowly and allowed—perhaps even forced—institutional learning. AI is diffusing faster than institutions can absorb.

Shared Anxiety, Divergent Legitimacy

Public opinion already reflects this mix of rapid adoption and institutional unease.

A Pew Research Center survey found that 50 percent of Republicans and 51 percent of Democrats say they are more concerned than excited about AI’s growing role in daily life.

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/11/06/republicans-democrats-now-equally-concerned-about-ai-in-daily-life-but-views-on-regulation-differ/

So, concern is bipartisan in the US. Trust is not.

The same survey shows sharp partisan differences in who people trust to set the rules: Republicans tend to trust the U.S. government (with Republican control, this is not surprising, motivated reasoning strikes again!), while Democrats are more comfortable with international bodies and foreign regulators (opposite previous parenthetical). People are worried in similar ways, but they disagree about who should be in charge.

That combination—shared anxiety and no consensus on who should decide—has historically been gasoline for politicization, and not just in the US.

How AI Becomes a Partisan Issue

The emerging legitimacy divide over AI governance maps cleanly onto existing partisan coalitions.

On the left, AI is likely to be framed as a labor and inequality problem: job displacement, corporate concentration, algorithmic bias, and the case for redistribution, antitrust, or worker protections. Democratic elites already emphasize AI safety, bias, and labor impacts, consistent with broader center-left political economy frames.

On the right, AI is more likely to be framed as an innovation and sovereignty problem: global competition with China, innovation speed, domestic regulatory authority, and skepticism of technocratic or international governance. Republican elites have increasingly emphasized AI as a strategic national asset and warned against overregulation that could slow U.S. competitiveness.

Gallup finds broad bipartisan support in the US for AI safety rules, but disagreement over whether government, industry, or international institutions should set those rules—suggesting that AI governance will become a contested partisan ownership issue rather than a consensus technocratic domain.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/694685/americans-prioritize-safety-data-security.aspx

In other words, AI will probably not invent new ideological divides. It will activate familiar ones: distribution versus dynamism, global governance versus national control, technocracy versus populist accountability.

AI will sort into partisan politics the same way trade and immigration did: not as a culture war (though there will definitely be some of that too), but as a political economy conflict.

Coalitional Fractures Inside the Parties

AI politics will not just divide Democrats and Republicans here in the US. It will likely fracture coalitions within each party.

On the Democratic side, AI is already creating tension between growth-oriented tech elites and labor-oriented populist factions. Silicon Valley Democrats emphasize innovation, national competitiveness, and industrial policy; labor Democrats emphasize job displacement, algorithmic bias, and corporate concentration. These are familiar fault lines, but AI compresses them into a high-salience policy domain.

On the Republican side, AI splits techno-nationalist elites from populist and culturally conservative factions. National security hawks and pro-business conservatives emphasize AI as a strategic asset in competition with China and oppose heavy regulation. Populist conservatives, by contrast, increasingly frame AI as a threat to jobs, cultural production, and domestic sovereignty, and express support for guardrails on deepfakes, data use, and corporate power.

Public opinion already reflects these cross-pressures. A YouGov survey found that roughly three-quarters of Americans favor more AI regulation, with majorities in both parties supporting stronger rules, suggesting AI governance will be a contested ownership issue rather than a purely deregulatory Republican cause.

https://today.yougov.com/topics/technology/survey-results/daily/2025/11/26/fc36f/1

Navigator Research finds that younger men and AI users are substantially more favorable toward AI, while older adults and women are more skeptical, creating cross-cutting demographic cleavages that do not map cleanly onto party labels.

https://navigatorresearch.org/views-of-ai-and-data-centers/

AI in the 2026 and 2028 Electoral Cycles

AI is already emerging as a campaign issue, and its political salience will likely accelerate through the 2026 midterms and the 2028 presidential cycle.

Candidates are beginning to campaign on electricity costs, data center siting, and AI-driven job displacement—issues that connect abstract AI debates to everyday material concerns. Polling shows overwhelming public support for government action on AI safety and data security, even at the cost of slower innovation, suggesting fertile ground for both populist regulation and technocratic governance agendas.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/694685/americans-prioritize-safety-data-security.aspx

By the 2028 presidential election here in the US, AI is likely to be framed simultaneously as an economic productivity engine, a national security imperative, and a distributional shock. These frames align with familiar partisan narratives but will be filtered through internal coalition struggles over labor, capital, sovereignty, and state capacity.

Adoption Without Trust

Another way of thinking about it: AI is being adopted faster than it is trusted.

Surveys suggest roughly one-third of Americans use AI tools at least weekly, but only a small minority express high trust, while large pluralities express skepticism or distrust.

https://yougov.com/en-us/articles/53701-most-americans-use-ai-but-still-dont-trust-it

Another YouGov poll found Americans increasingly believe AI will negatively affect society.

https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/52615-americans-increasingly-likely-say-ai-artificial-intelligence-negatively-affect-society-poll

Gallup surveys show roughly three-quarters of Americans expect AI to reduce the total number of jobs in the U.S. over the next decade.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/694688/trust-businesses-improves-slightly.aspx

This combination—rapid adoption paired with deep distrust—is historically unusual and politically unstable.

Historically, technologies become political when people can see and feel the costs. AI is becoming political while still accelerating.

This is uncharted territory, yes. But it still strikes me as territory we should try to map while we can.

The Censorship Paradox

AI will likely be politicized first through the information environment.

A US national survey by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and Morning Consult found voters deeply conflicted about AI in campaigns: majorities fear deceptive AI-generated content, but nearly half prioritize protecting free speech even if deception slips through.

https://www.thefire.org/research-learn/ai-and-political-campaigns-survey-toplines-june-2025

https://www.thefire.org/sites/default/files/2025/06/FIRE-AI-and-Political-Campaigns-Survey-Toplines-June-2025.pdf

Voters fear misinformation, of course. But they also fear regulators who decide what counts as misinformation.

This is not a technological problem. It is an epistemic (that’s fancy jargon for anything related to knowledge itself or “how we know what we know”) and institutional problem. When truth is contested, the power to label something “deception” becomes political and social power.

If this starts to sound like a low- to mid-grade Butlerian Jihad discourse—humans vs. thinking machines for you non-nerds—you’re not entirely wrong. But the real conflict won’t be religious technophobia. It will be institutional: who controls the machines, and who they answer to.

AI Is Not Just Cognitive—It Is Infrastructure

Most commentary treats AI as software because we really haven’t developed our language around AI yet. But thinking about it as software is analytically incomplete.

AI is an infrastructure technology. Every inference is backed by copper, turbines, transformers, cooling towers, and zoning boards.

Energy analyst Art Berman puts the point bluntly: modern societies increasingly treat electricity as a menu item—something you can order on demand—when in reality power systems expand slowly, expensively, and politically.

https://www.artberman.com/blog/complexitys-revenge-electric-power-and-ai/

Data centers currently consume a modest share of global electricity—around 1.3 percent today, projected to roughly 2.4 percent by 2030. But their political salience is outsized because they are geographically concentrated, inflexible loads that strain local grids, water systems, and land-use regimes.

Somewhere in Northern Virginia, a zoning board meeting about a data center will do more to politicize AI than a hundred white papers from Washington. That is usually how these things actually happen.

AI is not the dominant driver of electricity demand.

It is just the most visible one.

Once people can see and feel the costs, it goes beyond tech policy and becomes politics.

This framing is increasingly common among technologists themselves. A growing tech-policy discourse treats AI not as a software product but as a new foundational economic layer—closer to electricity or the internet than to an app. As Aakash Gupta put it in a recent thread on X, the real constraints on AI are no longer models or algorithms but energy, capital, and institutions.

That framing is politically explosive, because it means AI is not just a workplace tool. It is a macro-infrastructure shock that collides directly with utilities, zoning boards, labor markets, and national security doctrine.

Entry-Level Work as the Political Accelerant

The most politically explosive labor effect of AI is not mass unemployment per se. It is what I think of as “pipeline collapse.”

AI substitutes most easily for junior, transactional cognitive tasks: drafting, summarizing, coding, analysis. In this environment, senior professionals likely become more productive, yes, but junior roles become less necessary.

Gallup finds that AI use at work has nearly doubled in two years, with white-collar sectors leading adoption.

https://www.gallup.com/workplace/691643/work-nearly-doubled-two-years.aspx

OECD estimates that generative AI could automate or significantly augment tasks in 27 percent of jobs across member countries, with higher exposure in knowledge-intensive occupations.

https://www.oecd.org/employment/ai-and-the-future-of-work/

Entry-level work is not just income. It is status, mobility, and identity formation. Entry-level jobs are how people learn what a career even feels like. Remove that rung, and you don’t just slow mobility—you break the ladder.

Historically, blocked mobility pathways generate durable political cleavages by transforming status frustration into political identity. AI is compressing that process by narrowing entry points while accelerating competition for elite positions.

When the Builders Start Talking Like Political Theorists

One of the clearest signs that AI is about to become political is the way its builders are starting to talk.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, recently described AI as a kind of technological adolescence—a period where capability growth dramatically outpaces social and institutional adaptation. He has warned that advanced AI could displace large shares of entry-level white-collar work, concentrate wealth beyond historical precedents, and create political pressures that democratic institutions are not prepared to manage. It’s a long read too, but it’s worth it.

https://www.darioamodei.com/essay/the-adolescence-of-technology

That is not a startup pitch. That is structural political economy analysis.

When the people selling the technology start warning that institutions cannot absorb it, you should assume institutions will soon respond—poorly, noisily, and politically.

Elite Consensus, Mass Divergence

At the elite level, AI currently generates unusual—perhaps temporary—convergence: elites broadly treat AI as a strategic asset for national competitiveness, defense applications, productivity gains, and industrial policy.

Mass politics is unlikely to follow that script though.

Even elite consensus tends to fracture once costs become salient to mass publics: power bills, outages, water fights, land-use battles, visible job displacement. AI will likely follow the same trajectory as trade or immigration policy—technocratic consensus at the top, populist backlash at the bottom.

The speed of diffusion compresses all of this into a much shorter political cycle. Institutions usually adapt before distributional effects become politically salient. With AI, distributional effects arrive first.

This dynamic also maps onto what Peter Turchin calls structural-demographic theory: when upward mobility slows, elite aspirants proliferate faster than elite opportunities, and institutions lose legitimacy, political instability becomes more likely. In Turchin’s framework, blocked mobility and elite overproduction are not just economic problems; they are drivers of polarization, populism, and institutional crisis (Turchin 2016; 2023).

What is striking is how closely this emerging tech-elite discourse maps onto structural political theory. Amodei’s “technological adolescence” is, in political economy terms, a period where productive capacity grows faster than institutions, norms, and legitimacy frameworks.

That is structurally similar to Turchin’s model of instability: rapid change expands elite aspirations and expectations while narrowing stable pathways, producing frustration, intra-elite conflict, and legitimacy crises. Turchin modeled this over centuries. AI may compress the same dynamics into a decade.

To the extent AI compresses entry-level pathways while credentialing and elite aspirations continue to expand, it plausibly accelerates these structural-demographic dynamics. AI looks like a structural-demographic shock compressed into a technological form: it increases the number of people with elite aspirations while narrowing the pathways to elite status—a classic recipe for intra-elite conflict and broader political turbulence.

It is worth noting here that much of the AI research frontier is deeply optimistic. For example, in a recent piece by Soubhik Barari that is really worth a read if you’re a social scientist, recent work catalogs dozens of ways AI could expand simulation, forecasting, survey design, and causal inference—effectively turning social science into a much more experimental and computational discipline.

This knowledge production upside is very real. But knowledge production capacity and political legitimacy are not the same thing. Even technologies that dramatically improve knowledge can still destabilize institutions when their distributional and governance consequences outpace trust and adaptation.

Recent empirical work underscores this. A large-scale analysis of more than 40 million scientific papers finds that AI increases individual researchers’ productivity and citation impact but narrows the collective exploration of scientific ideas, pushing scientists toward similar problems and reducing the diversity and interconnectedness of research trajectories.

https://www.science.org/content/article/ai-has-supercharged-scientists-may-have-shrunk-science

In other words, AI appears to amplify individual knowledge production capacity while potentially shrinking the research frontier at the system level. This is exactly the institutional risk profile that matters for politics: concentrated private gains and more fragile public institutions.

It comes to this: AI will likely be the most powerful (social and myriad other) science instrument ever built—and simultaneously one of the most destabilizing political technologies ever deployed.

Crypto as the Sidecar Politics of AI

Cryptocurrency is not completely central to the AI story, but it is a related technology (especially in the eyes of those putting together crypto policies in this current moment, e.g., the US Senate’s “Digital Asset Market Clarity Act”) and it also serves as an early warning signal of what happens when a general-purpose technology collides with political institutions before governance frameworks are in place.

Crypto produced a decade of hype cycles, scandals, ideological/partisan sorting, and regulatory improvisation, with (so far) limited resolution of core legitimacy and regulatory questions.

Artificial intelligence is likely to follow a similar political trajectory, but on a vastly faster diffusion curve.

AI’s Adoption Curve vs Crypto’s

As we saw in the table up above, crypto diffusion has been slow and uneven.

Global estimates suggest roughly 6.8 percent of the world’s population owns cryptocurrency, about 560 million people.

https://www.triple-a.io/cryptocurrency-ownership-data

In advanced economies, roughly one in five adults report owning crypto, but regular transactional use remains far lower.

https://www.gemini.com/blog/introducing-the-2025-global-state-of-crypto-report

Crypto has had more than a decade to diffuse. AI has reached mass habitual use in two years. Amazing.

The political system can absorb slow, secular technological diffusion.

It cannot absorb fast diffusion.

Identity, Incentives, Regulatory Style—and Digital Rights

Ok, Saunders, why have you mentioned crypto so much? Well, here’s the payoff.

Crypto previewed three governance conflicts AI will scale:

Identity and surveillance. Proof-of-personhood systems, biometrics, and digital identity infrastructure promise to separate humans from bots and enable trusted online spaces. They also raise civil-libertarian fears of pervasive surveillance and state or corporate identity regimes.

Tokenized compute, data, and incentives. Efforts to finance AI infrastructure through tokens and data markets will revive familiar conflicts over consumer protection, financial regulation, and the ownership of digital labor and data.

Regulatory style. Federal preemption versus fragmented state experimentation will become a core ideological cleavage, echoing crypto’s patchwork governance battles but with higher stakes.

These conflicts converge on a broader and more politically salient domain: digital rights.

As John Robb has been (correctly) hammering on about for years now, AI systems are increasingly implicated in privacy, due process, speech, and labor rights. Questions that once belonged to speculative tech ethics are becoming legal and constitutional disputes: Who owns training data? Do citizens have a right to explanation? Can governments mandate identity verification? Can employers delegate managerial authority to algorithms?

Crypto was treated as a niche financial curiosity, and it may be becoming more than that. But still, it was actually a governance stress test to see how we deal with new technologies.

AI is that stress test on lots of steroids, but mainstream, and it obviously touches core constitutional domains.

Procedural Politics Before Substantive Politics

When new technologies diffuse slowly, societies debate values before consequences become unavoidable. When technologies diffuse rapidly, societies argue about procedures while consequences unfold in real time.

AI is the latter case.

Phase 1: Procedural Governance Under Diffusion Shock

The first wave of AI politics will focus on how AI is used rather than what society should become.

Expect intense debate over:

Disclosure and watermarking rules for AI-generated content

Government procurement standards

Liability frameworks for algorithmic decisions

Zoning and permitting for data centers and grid infrastructure

Workforce retraining programs, tax credits, and wage insurance

These debates map onto existing institutional structures. They do not require rewriting the social contract.

Procedural politics is how democracies stall for time when technology moves faster than institutions.

Phase 2: Distributional Politics in a Compressed Timeline

Once entry-level labor markets narrow, productivity gains concentrate, and infrastructure costs become visible, procedural politics will be insufficient.

Substantive questions follow:

Should education systems be redesigned when AI collapses the value of certain cognitive/knowledge skills?

Should entry-level labor markets be subsidized or reconstructed?

Should AI-driven productivity gains be taxed to fund wage insurance or universal benefits?

Should certain decisions be prohibited from automation regardless of efficiency?

These are not regulatory tweaks. They are big political economy choices.

Historically, societies delay these debates until crisis forces them. AI’s diffusion curve compresses that delay.

Trigger Conditions Under Rapid Diffusion

Substantive AI political conflicts will accelerate if any of the following occur:

A visible employment shock (rapid white-collar layoffs tied to automation).

A substantial infrastructure failure (grid outages or water conflicts tied to data centers).

A democratic legitimacy crisis (AI-driven election interference or large-scale disinformation).

Geopolitical escalation (national security framing overriding domestic consensus).

Diffusion speed makes these triggers more likely to occur before institutions stabilize.

Complexity’s Revenge

Berman frames AI as a case study in complexity outpacing physical and institutional capacity. Societies add layers of technological complexity faster than they can maintain the systems that support them.

Joseph Tainter argued that collapse is simplification when complexity yields diminishing returns. Collapse is probably not the right baseline. A slow erosion of institutional legitimacy is.

Institutions will increasingly delegate decisions to systems they cannot fully explain or defend, while citizens experience rising costs, blocked mobility, and opaque governance.

AI is not just a productivity technology, then. It is a test of whether existing institutions can absorb rapid technological change.

Why Liberal Democracies Are Structurally Bad at Fast (GPT) Transitions

Liberal democracies are optimized for incremental change. They rely on veto points, layered authority, and slow consensus formation to prevent catastrophic error.

That design is great for democratic stability. It is terrible for technologies that move this quickly.

North, Wallis, and Weingast (2009) argue that modern states stabilize social orders through institutionalized rule systems that constrain violence and rent-seeking. Those systems are inherently slow-moving because they require broad elite and mass legitimacy.

AI compresses technological change into timelines that outpace institutional legitimacy formation.

Premature Delegation

One emerging institutional response to complexity is delegation: algorithmic decision systems, AI-assisted governance, and automated bureaucratic triage.

This is rational. Of course, it, too, is also destabilizing.

Institutions that cannot explain or justify delegated decisions to citizens lose credibility. When credibility erodes, legitimacy becomes procedural and fragile rather than substantive and trusted.

AI is not just a productivity tool. It is a mechanism through which institutions delegate decisions they can no longer manage themselves.

This is the institutional analogue of what political theorists have long warned about: authority that cannot justify itself increasingly relies on procedure rather than consent.

Structural Political Trajectory

Liberal democracies will likely respond to AI in three stages (this, too, should be its own piece and probably will be in the future…):

Technocratic improvisation (lots of white papers, task forces, and pilot programs).

Populist backlash (as costs hit voters faster than benefits).

Institutional reconfiguration (once a new coalition locks in a settlement).

The speed of diffusion determines how chaotic this transition becomes.

AI’s diffusion curve suggests it will be fast.

If this starts to sound less like a policy debate and more like a civilizational phase transition, that’s because it probably is. The tech industry is starting to describe AI in the language of political theory, while political institutions are still treating it like software policy.

Historically, that mismatch is how technologies become political—abruptly and with very little warning.

To Sum Up The Core Thesis

Everything is moving so fast. We all feel it and are living it.

Trying to look forward from here is so so difficult in such wildly uncharted territory, and I hope that this exercise isn’t in vain.

Writing this thing has felt like squeezing sand in your hand and watching it slip through your fingers. I don’t like that feeling either.

That said, after all this, I think it’s obvious that AI will change politics. I also think that AI politics will not polarize because of new ideologies, but it will polarize along existing cleavages—with new twists. And that is because AI is becoming a legitimacy stress test for institutions that already struggle to command trust.

Every transformer installed, every zoning board fight, every displaced junior analyst, every mindblowing innovation that feels threatening, all will make AI less abstract in our lives, and therefore more political.

Crypto is an interesting comparison because it offered a slow, almost ignorable rehearsal for this kind of governance conflict. AI will be the fast version that arrives before institutions have fully learned the lesson.

Liberal democracies were built to manage slow-moving general-purpose technologies. Artificial intelligence is arriving on a timeline that compresses adaptation into a handful of election cycles.

The medium is perhaps no longer just the message, as McLuhan said.

It is the power grid—and, eventually, the zoning board meeting—and, then the unemployment/UBI line.

Future Work: Mapping the Political Economy of AI

This essay sketches what is really a framework rather than a comprehensive theory, but I had to stop somewhere and put a bow on this thing so it could get out there and hopefully help all of us think about these things rigorously.

That said, several research directions have come to mind that deserve sustained treatment. Just some ideas that someone should explore…

Comparative political responses to AI diffusion. Cross-national variation in institutional trust and welfare regimes may mediate AI politicization.

AI and education as a political cleavage. Credentialing, assessment, and elite versus mass education may become a core AI political fault line.

Capital concentration and techno-oligarchy. AI compute and data are highly concentrated among a small number of firms; the political consequences are under-theorized.

Geopolitics and AI nationalism. Export controls, compute nationalism, and U.S.–China technological competition could reshape domestic AI coalitions.

Cognitive polarization and AI risk perception. Motivated reasoning may structure AI attitudes independently of material interests.

You made it! The truth is that I had no idea how to even stop with this piece. It could have been a whole bunch of different pieces, but at least now I have a mind map and so do you!

The AI rabbit hole is DEEP, friends. Good luck to us all.

If you enjoyed (hated) this piece, please restack or share it with someone who you think would appreciate (hate) it. Thanks. :)

Also, I’d love to hear your thoughts about angles that I haven’t thought of yet, I’m sure there are many.

Great insights and thanks for the shoutout! Very interesting to map AI attitude onto the growing realignment of coalitions. Good reminder of how expansive AI is as a *social* technology and the way it can be centrally framed / understood along many more dimensions (e.g. labor automation, companionship device, centralized form of elite media) than the other mass technologies you listed. Dimensions that obviously map onto political cleavages, arguably way stronger than when those other technologies were introduced.

Curious if you have any takes on what a dot-com-bubble-esque AI crash would do to the political economy you've described here. Probably above all our paygrades, but would be interesting to write about, taking the lessons/comparisons to the Internet further.

This nails why the crypto comparison keeps coming up everywhere. The procedural-before-substantive politics framing really clicks, especialy when you map it against how fast entry-level roles are already evaporating. I've watched junior colleagues get reassigned because AI tools can now handle their entire workstream, and it's happenning way faster than anyone expected a year ago.