Propaganda, Activism, and Why Beautiful Trouble's Tactics Work

Why Certain Political Tactics Recur Across Movements and Ideologies

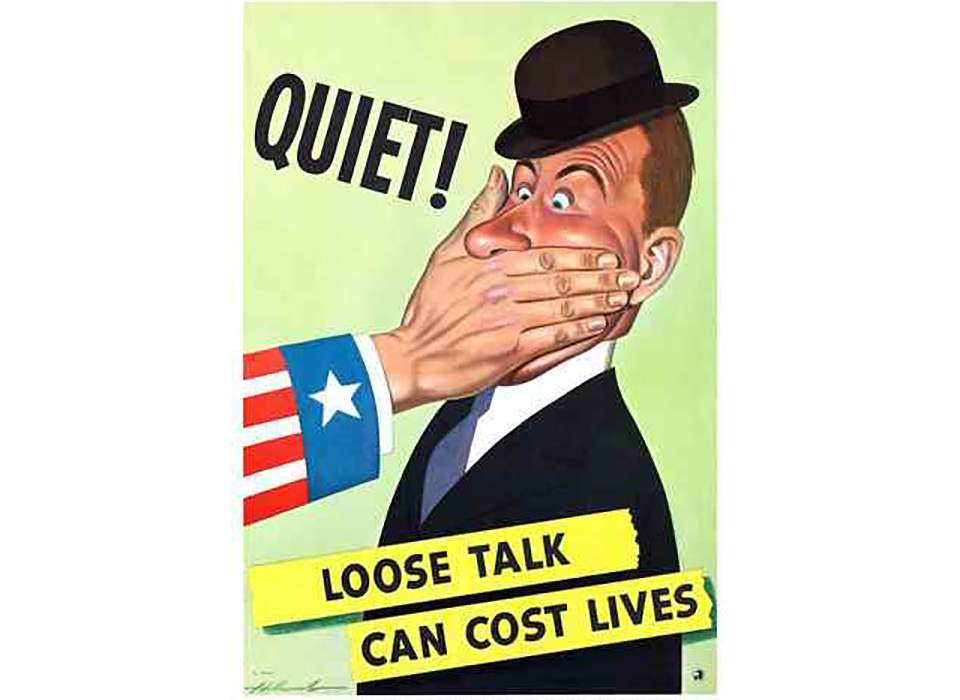

In a previous essay, I argued that propaganda is (a) ubiquitous and not a pathology of authoritarian systems per se, and (b) a normal feature of mass politics—and that being more conscious of those two facts can help us slow down our reactions to it in real time. What separates democracies from authoritarian regimes is not the absence of propaganda, but whether persuasion remains pluralistic, contestable, and constrained by institutions that still function as referees.

This post extends those ideas by digging into the political psychology of why these tactics work so reliably.

If propaganda operates through identity, affect, incentives, and attention, then we should expect the same underlying mechanics to show up in other domains that reliably shape political outcomes—especially activism. And indeed they do. Again and again. Across ideologies, countries, and historical periods.

That recurrence is the clue worth paying attention to.

When similar tactics reappear independently in very different movements—labor, civil rights, environmentalism, populism, reactionary politics—it’s a strong signal that we’re not looking at ideology. We’re looking at mechanism.

And to be clear from the start, this is not an argument against activism. It’s an attempt to explain why certain activist playbooks are so effective—and why, under modern conditions, they increasingly place strain on democratic institutions designed for much slower, more procedural forms of contestation.

Why These Playbooks Keep Reappearing

Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals.

Beautiful Trouble.

Gene Sharp’s writings on nonviolent action.

More recent digital organizing manuals.

These texts are often treated as ideological artifacts. I’d argue that they aren’t. Instead, they are operational manuals, meaning they are collections of heuristics that exploit predictable features of human psychology, media incentives, and institutional vulnerability.

The reason they keep resurfacing is simple. They really work.

If a tactic works across left and right, democratic and authoritarian contexts, moral and immoral causes, then its effectiveness cannot depend on the righteousness of the cause. It depends on the structure of the environment it operates in.

Increasingly, that environment is one in which attention is scarce, identity is salient, institutions move slowly, and the media reward conflict over process rather than deliberation.

Activism Is Not Persuasion (At Least Not Primarily)

A useful distinction here is between persuasion and constraint.

Persuasion operates inside shared procedural legitimacy. You argue, provide evidence, appeal to norms, and accept adverse outcomes as binding. Persuasion assumes referees that are broadly accepted as legitimate.

Effective activism often does something different. It raises the cost of inaction for institutions and elites until normal procedures are no longer tenable. It forces action outside routine channels.

That doesn’t make it illegitimate. But it does mean it operates on a very different logic.

Successful activism does not usually win debates. Rather, it makes neutrality expensive.

This is where the connection to propaganda becomes clearer. Both activism and propaganda rely less on convincing individuals through deliberation and more on shaping the environment in which decisions are made—what is salient, urgent, shameful, or reputationally dangerous.

The Psychological Mechanics (Before the Politics)

Before naming specific movements or texts, it’s worth laying out the mechanics themselves. None of these require deception. None require centralized coordination. They emerge naturally from incentives.

Moral Simplification. Complex systems are reduced to moral binaries. This lowers cognitive load and increases emotional engagement. Procedural nuance is displaced by urgency.

Identity Activation. Issues are framed as tests of who you are, not what you think. Once identity is engaged, motivated reasoning does most of the work.

Asymmetric Cost Imposition. Institutions bear reputational and operational costs that activists do not. Escalation is cheap on one side and expensive on the other.

Affective Salience. Anger, fear, outrage, and moral clarity spread more effectively than technical detail. Media systems select for these signals.

Narrative Compression. Symbols, slogans, and vivid incidents crowd out slow-moving contextual explanations. What sticks is what is emotionally legible.

These are not bugs. They are features of human cognition interacting with modern media.

Alinsky Was Right About the Mechanics

Saul Alinsky is often read as a political thinker. I think he is better understood as someone who diagnosed institutional weaknesses.

In institutions structured this way, ridicule works because authority is reputationally fragile, personalization works because institutions cannot respond symmetrically, and disruption works because it forces action outside procedural norms, often by making inaction uncomfortable. All of these dynamics are inseparable from institutional legitimacy, which is precisely why they become points of leverage.

Alinsky understood that legitimacy is a core institutional vulnerability. Institutions rely on compliance, deference, and shared norms. When those norms are attacked faster than they can be defended, institutions lose their ability to function as referees.

You don’t have to endorse Alinsky’s politics to recognize the accuracy of that diagnosis.

Beautiful Trouble as an Optimization Manual

Beautiful Trouble is often read as a handbook for creative protest. It is more revealing to read it as a user experience manual for attention economics.

It optimizes for media visibility, emotional resonance, identity signaling, and rapid diffusion under modern attention constraints.

In that sense, it sits squarely inside the same incentive landscape as modern propaganda. It treats institutions as brittle systems with predictable failure modes, and it teaches activists how to exploit those modes efficiently.

Again, this is not a moral claim. It’s a structural one.

Why Institutions Keep Losing These Fights

This is where the democratic tension emerges.

Institutions move slowly, are norm-bound, must justify decisions procedurally, and often lose legitimacy when they escalate affectively.

Activists tend to move quickly, frame issues in moral terms, exploit asymmetries, and are often rewarded for escalation.

This is not primarily a failure of institutional communication. It is a mismatch between institutional logic and attention economics.

Democracies were not designed for permanent mobilization. They were designed for pressure followed by restraint.

AI and Automation Will Amplify All These Dynamics, BTW

One additional pressure is worth noting, because it may amplify all of these dynamics. Large-scale changes in work, status, and daily structure—accelerated by automation and artificial intelligence—are likely to increase the number of people with more time, weaker institutional attachment, and fewer material or social stakes in existing arrangements.

As scholars like Peter Turchin have argued in other contexts, populations that experience this kind of surplus or immiseration tend to become politically volatile, not because they are irrational, but because the ordinary constraints that dampen escalation begin to erode.

In that environment, activism becomes cheaper, pressure politics more attractive, and institutional legitimacy even harder to sustain.

Is This Fifth-Generation Warfare (5GW)?

At this point, it’s tempting to reach for the language of “information warfare” or “fifth-generation warfare.” That language can mislead if taken too literally, but the analogy is useful if translated into civilian, non-paranoid terms.

Fifth-generation warfare is not about tanks or secret plots. It’s about conflict over legitimacy, perception, and institutional trust, where the primary terrain is cognitive and social rather than territorial.

Seen this way, many activist and propagandistic tactics resemble 5GW not because activists are soldiers, but because both operate in the same terrain: identity, narrative, and institutional credibility.

Crucially, none of this requires centralized intent. These dynamics can be:

state-driven,

movement-driven,

platform-driven,

or fully emergent.

When epistemic exit becomes costly—when leaving a narrative carries real social or identity penalties—persuasion begins to function like constraint even without coercion.

That’s the danger zone.

From Activism Back to Propaganda

This brings us back to the argument of the previous post.

Propaganda becomes dangerous not when it exists, but when it stops being contestable—when narrative competition collapses and institutions lose legitimacy as referees.

Activist tactics and propaganda share many of the same mechanics. The difference is direction and scale. When these tactics become ambient and closed-loop, pluralism exists formally but not experientially.

At that point, democratic friction fails and things go off the rails—whether it’s a bit or a lot depends on the strength of and the amount of trust in our institutions.

The Democratic Question

The question is not whether these tactics should exist. They are a permanent feature of mass politics, and under modern conditions—faster discourse, moralized conflict, and asymmetric incentives—they are becoming more effective, not less.

The harder question is whether democratic institutions are resilient enough to absorb that seemingly-increasing pressure without breaking. Can they still function as legitimate referees in an accelerating political environment optimized for attention, identity, and escalation?

This is why democracy is not defined by the absence of propaganda. It is defined by the continued existence of counter-propaganda, institutional contestation, and procedures that remain binding even when outcomes are contested.

When those constraints erode, persuasion gives way to pressure, legitimacy gives way to power, and politics begins to operate on a very different logic.

Excellent framing of activism as cost imposition rather than persuasion. The distinction matters bc it helps explain why institutions keep losing these fights even when they have better arguments. I've seen this play out in corporate contexts where reputational asymmetry means one viral moment can override months of procedural legitimacy. The part about AI amplifying thesedynamics is understated but probably the most consequential point here.

Decentralized power, from mass access to powerful technological tools such as the Internet or firearms only accessible to the elites, to the rise of distrust-driven populist political institutions (liberal democracy) has resulted in the rise of activism, corruption, legal grey zones, and other means of hard power by the masses that institutionalists (read- liberal authoritarians) hate, as they transfer real power away from centralized power to individuals.

This is a dynamic shift that has been emerging since the 18th century, but has significantly accelerated in the 21st century- power in the future will likely not vest in a political elite- states, aristocracies, international institutions, corporations- but will increasingly be vested in the individual who simply becomes more and more naturally powerful thanks to cheap technological innovations.

Much like how it is very easy to escape censorship and ID verification on the internet, with technologies such as Tor or VPNs, it will be impossible for institutions to clamp down on activist culture, as the populist masses continue to erode power from all forms of elite institutions.

I would emphasize, again, that this is a natural process that is the result of technological advancement empowering the individual (making powerful technologies such as communication readily available and hard to regulate). Elite institutions are widely seen by individuals as a necessary evil, and therefore only tolerated because the individual must. When the individual no longer depend on them or the individual can escape their punishment for infractions of their rules, the elite institutions cease to hold any power, and fade away, much like the British monarchy transitioning from a divine-right driven absolute monarchy to today a merely token symbolic constitutional monarchy.